Follow the hopes and dreams of four generations of a Korean immigrant family beginning with a forbidden love and crescendos into a sweeping saga that journeys between Korea, Japan and America to tell the unforgettable story of war and peace, love and loss, triumph and reckoning.

Horoomon: the Japanese word for grilled offal, derived from "something to be thrown away." There were people who picked up discarded animal intestines and ate them—Koreans who moved to Japan during the Japanese colonial era. The Japanese looked down on them for grilling and eating offal, but today, it has become a beloved dish for all. For Zainichi Koreans who have lived in Japan, horomon carries the sorrows and history of their lives.

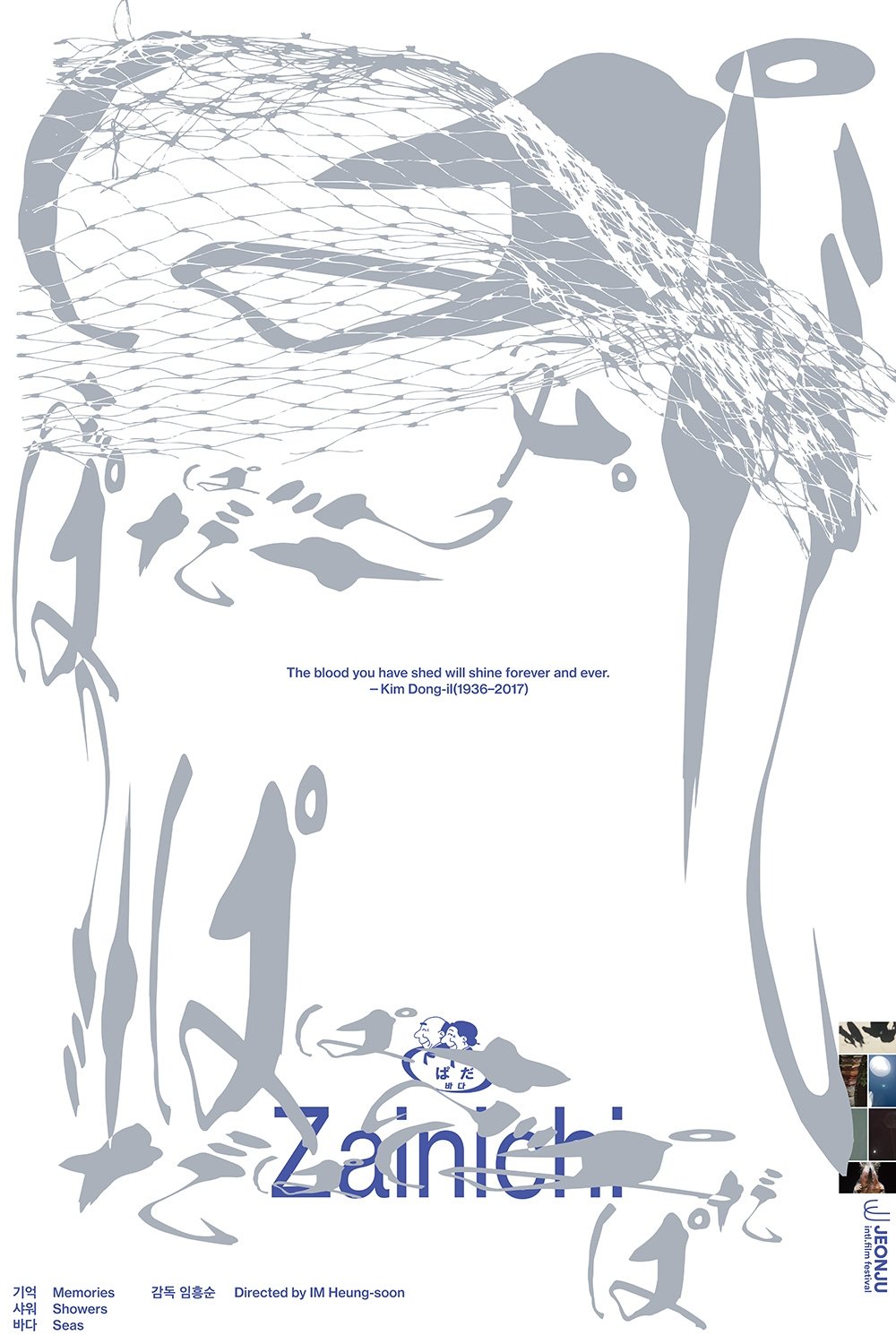

The late Kim Dong-il, a Jeju April 3 refugee in Japan, left behind over 2,000 crocheted items and pieces of clothing that preserved her memories, identity, and history. As the film traces the redistribution of her belongings, it illuminates the still-unhealed lives of various Zainichi Koreans who lived through the same era, sharing and connecting their intertwined memories.

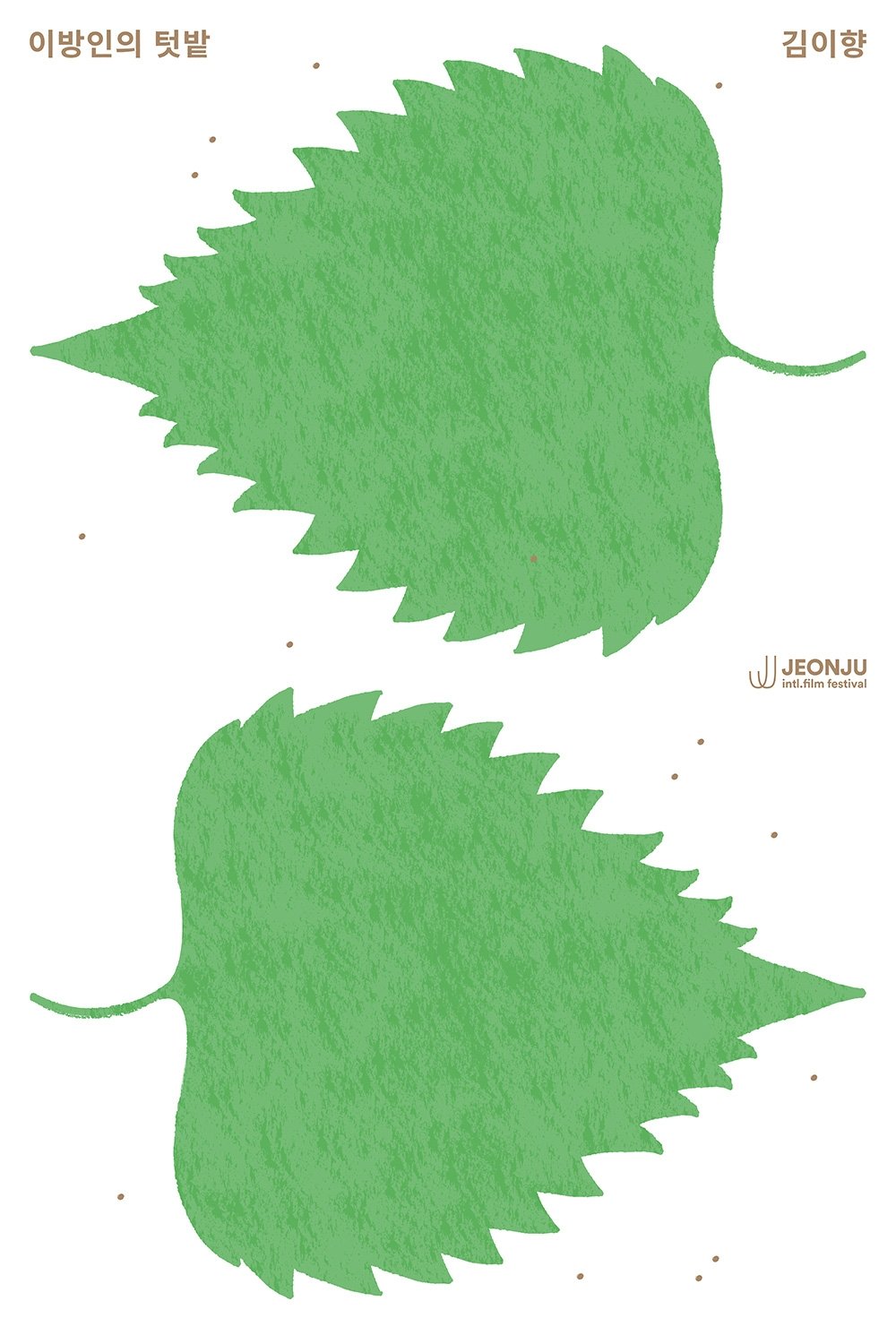

A Japanese herb called 'shiso' looks like a perilla leaf but has a unique fragrance. It's like how I have a Korean name and nationality but still feel a sense of alienation in Korean society. The death of my grandmother, a first-generation Zainichi, raises a question for me: Does death also mark the end of the life of an outsider? In the end, where do we return to?

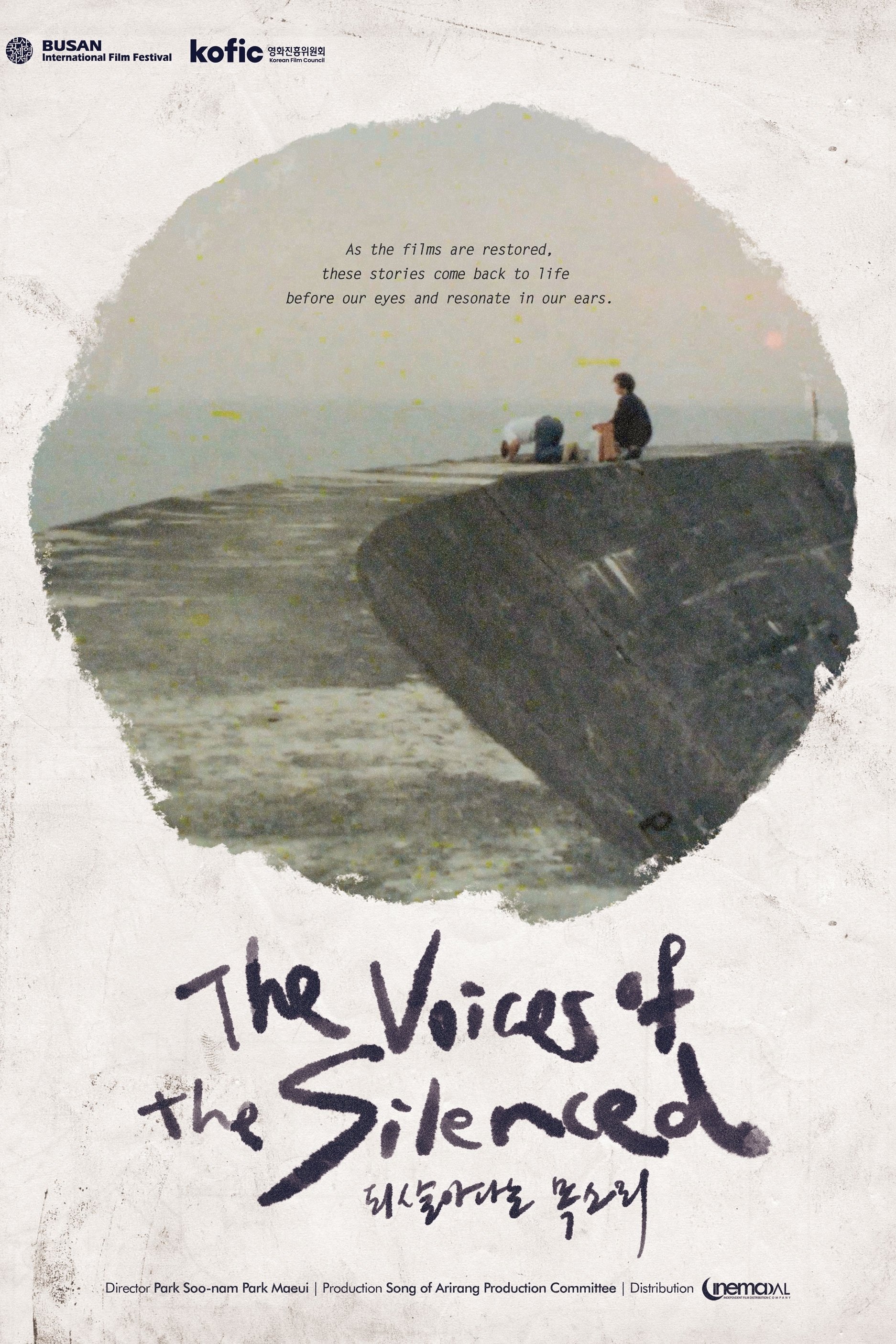

Director Park Soo-nam, a second-generation Korean resident in Japan who is losing his eyesight, decides to digitally restore 16mm film she shot a long time ago, relying on her daughter Park Ma-eui's eyesight. The blood, tears, and numerous corpses of Koreans living in Japan are clearly engraved in the film filmed over 50 years.

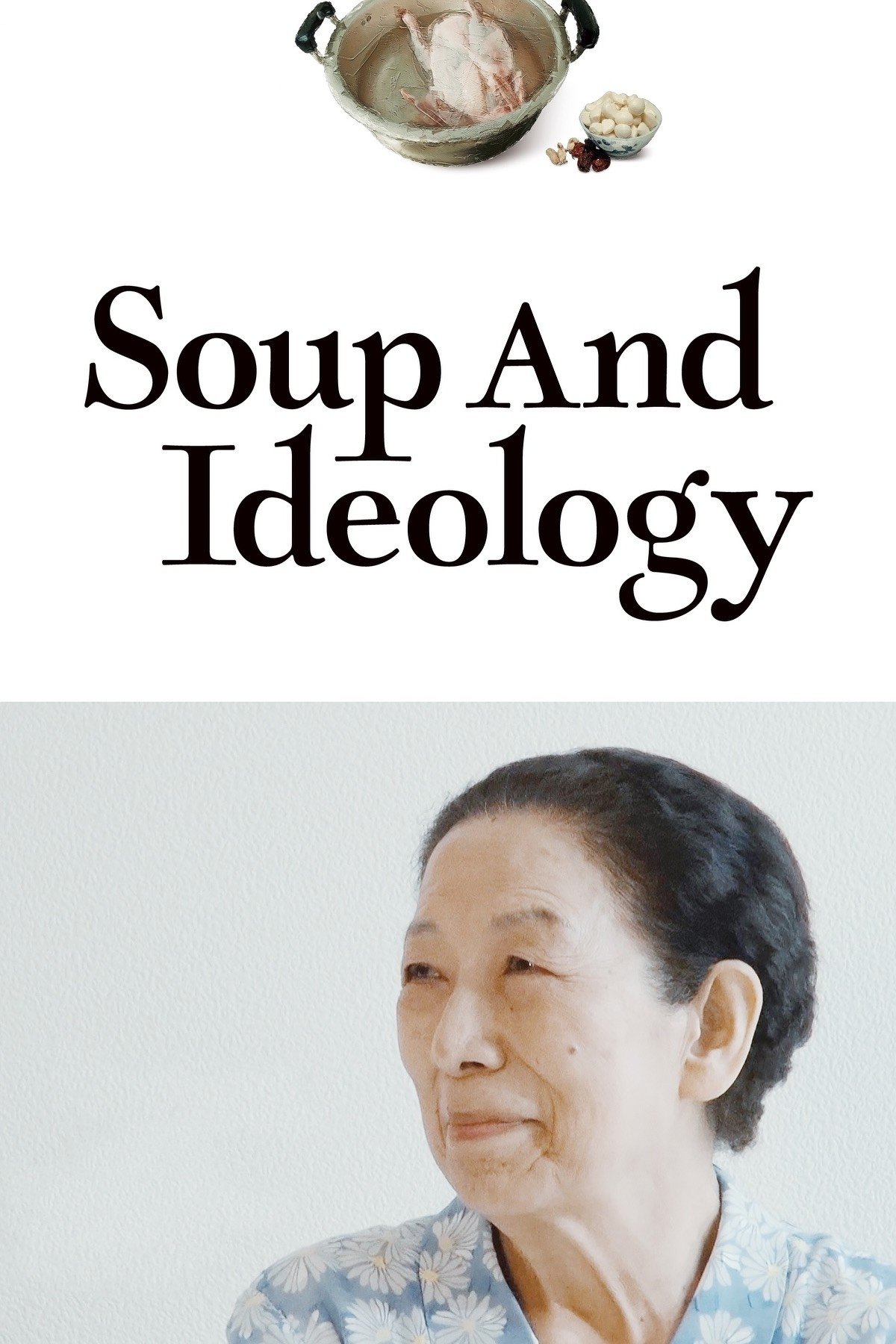

Confronting half of her mother’s life—her mother who had survived the Jeju April 3 Incident—the director tries to scoop out disappearing memories. A tale of family, which carries on from Dear Pyongyang, carving out the cruelty of history, and questioning the precarious existence of the nation-state.

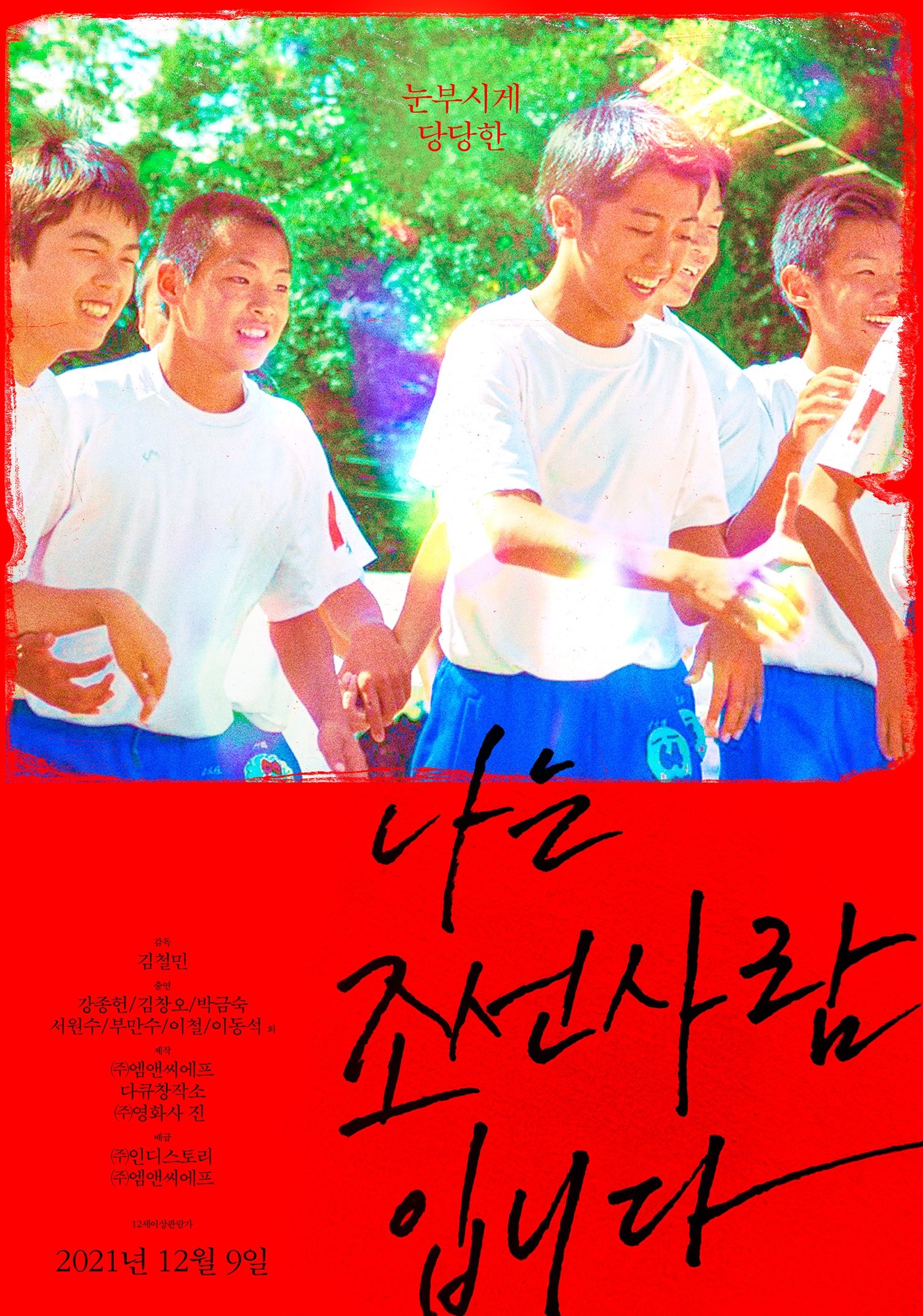

After 15 years of knowing Chosun people in Japan I met on Mt. Geumgang in 2002, I face the history of colonization and division that I had not known before. They’ve been to North Korea many times, but never to South Korea. They tell us why they want to live as Chosun people despite the discrimination in Japanese society.

A retired contract killer goes on a bloody rampage when a young girl finds herself at the mercy of gangland human traffickers and only one man can come to her rescue, with an arsenal of weapons and years of experience in the art of killing.

The protagonists of the film are the Zainichi Korean women living in Kawasaki. They were tossed about by the war, and after many trips to and fro across the sea in search of a place to live, they finally arrived in Kawasaki, where they have lived modestly and vigorously.

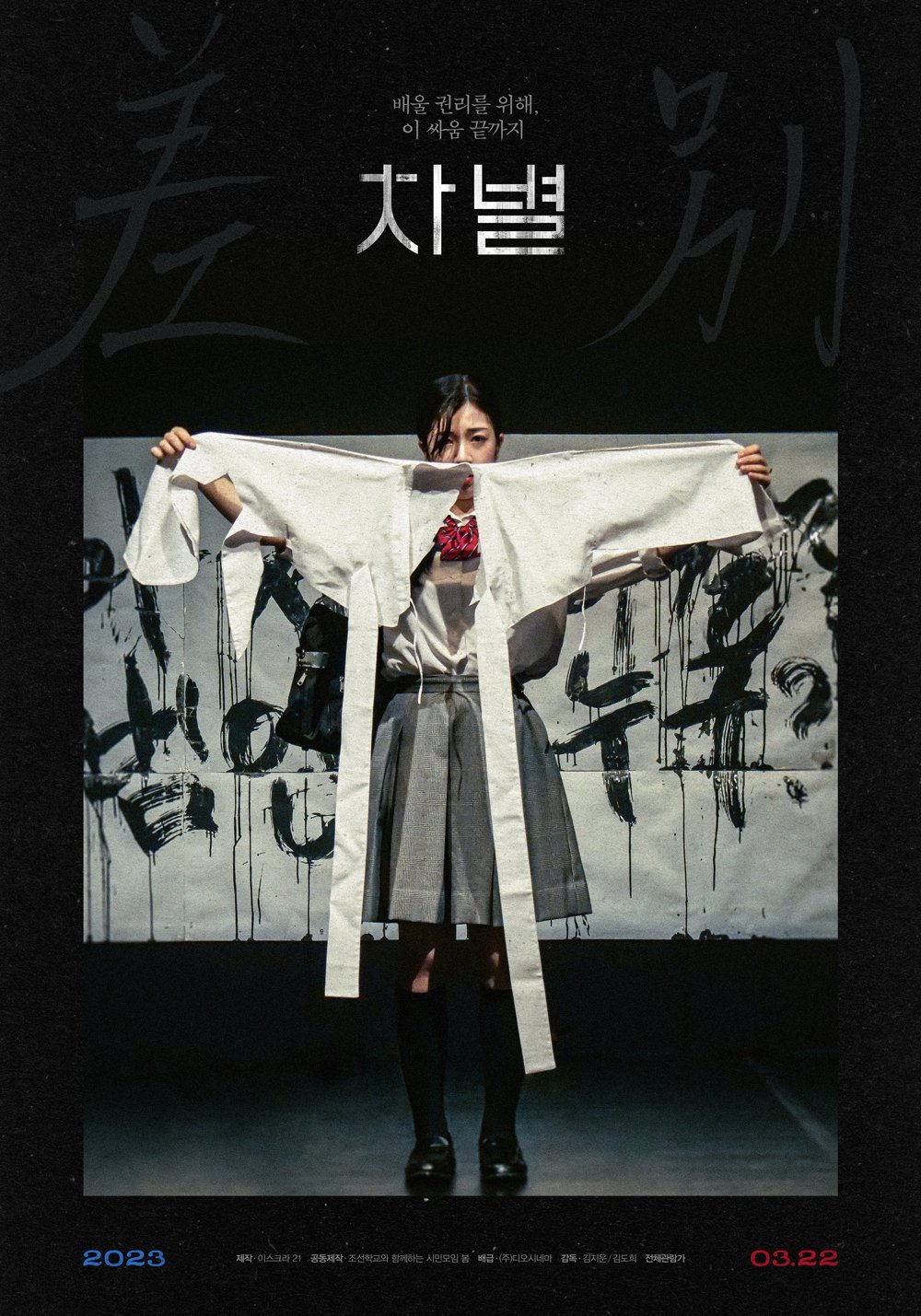

Since 2013, Japan has implemented the free high school policy. However, only 10 Chongryon Korean high schools are excluded from this policy. The reason is that there are suspicions that the grant for free education will be misused by Chochongryon and others. Five of these schools protested about this measure and filed a claim for damages against the government in 2013. After four years of hearings, the first trial decision was made on July 19, 2017, starting with the case of Hiroshima Chongryon Korean high school.

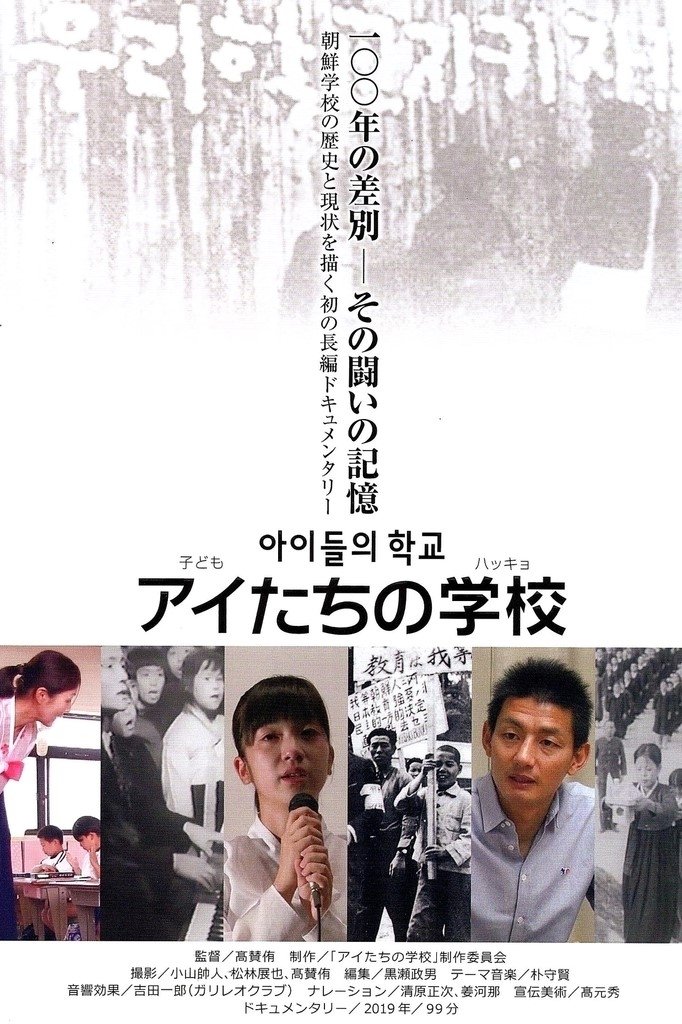

In 1948, after the Japan’s defeat, the General Headquarters and Japanese government ordered that the Chosen gakko, schools for Koreans in Japan,ō be shut down. Koreans in Osaka strongly resisted, and 16-year-old Kim Taeil was even shot and killed by the police. This was the Hanshin Education Incident. 70 years have passed, but the Japanese oppression continues. They've removed the Chosen gakkoō from being eligible for free education. Gaining strength from the growing hatred from the conservatives, the Abe administration is misusing the educational issue as a means to cause political strife. In the midst of ongoing conflicts in Japan, nonfiction writer KO Chanyu has directed Korean Schools in Japan, compiling a history of the Koreans' fight for education.

Set in the 1970's in the Kansai region of Japan.. Yong-Gil is Korean, but he moved to Japan and settled down. He runs a small restaurant named Yakiniku Dragon. He is married and has three daughters: oldest daughter Jung-Hwa, middle daughter Yi-Hwa and youngest daughter Mi-Hwa. Oldest daughter Jung-Hwa is dating Tetsuo, but they break up. Middle daughter Yi-Hwa loves Tetsuo and marries him, but Tetsuo still loves her older sister and they divorce. Youngest daughter Mi-Hwa wants to become a singer, but she is in love with a married man.

Imman Kim wants to reconcile with his parents, who emigrated to Osaka after April 3 Jeju Uprising. Cheolwoong Park has supported his younger sister during his entire life, blaming his father who moved to Tokyo to avoid guilt-by association. Soonam Park has devoted her life to human rights movement for a second-generation Korean-Japanese and her daughter Mayi Park who also lives as a Korean-Japanese. This film tell us about meaning of a nation through their life stories.

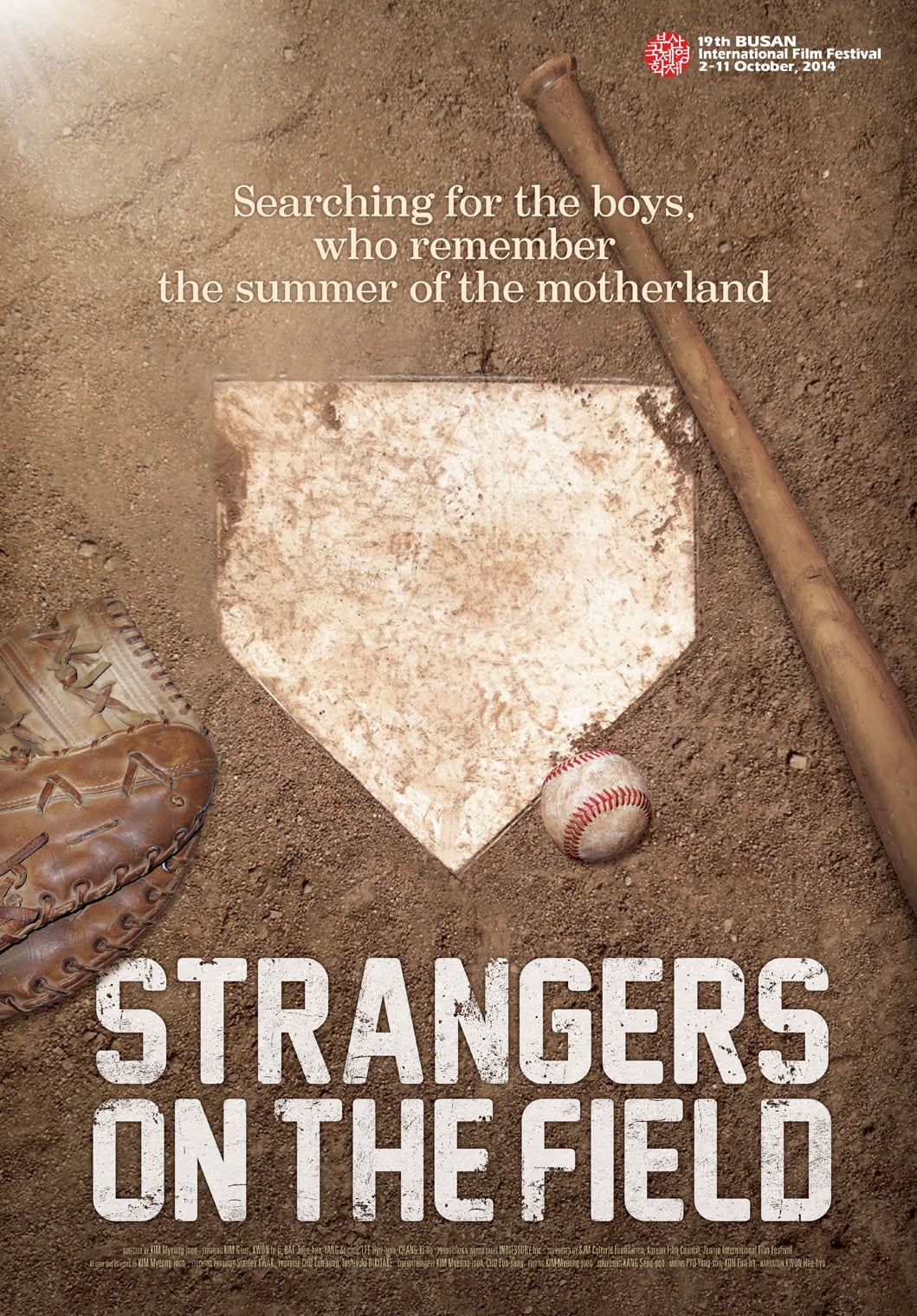

In April 2013, unfamiliar faces appear at the Jamsil Baseball Stadium during the opening matches between Doosan and SK. The nervous middle-aged men throwing and batting the first ball are, in fact, Korean-Japanese former team members that played on that same spot in the 1982 finals of the Bong-hwang-dae-ki games.

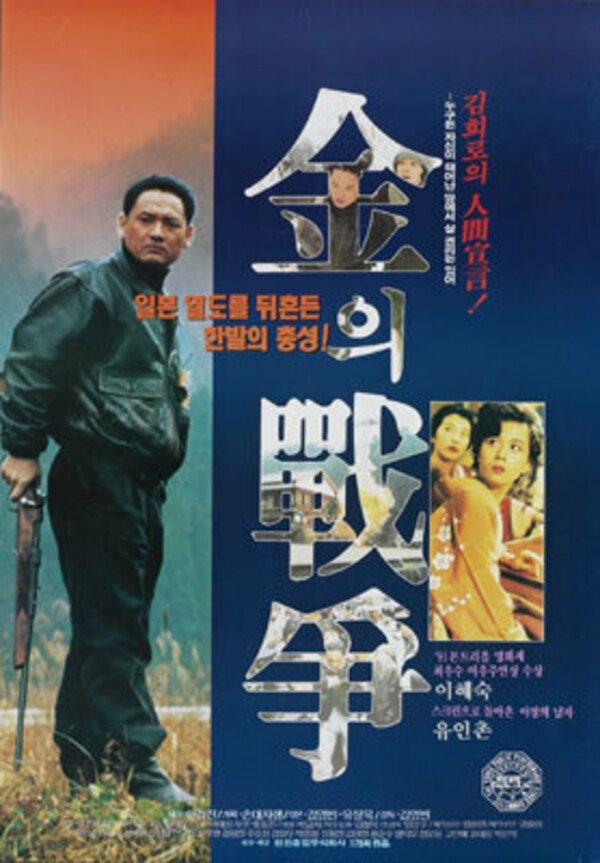

This is the true story of Kim Hee-ro and his fight for justice in Japan. On February 20, 1968, two Japanese gangsters were killed in a cabaret in Shizuoka, Japan. Kim Hee-개, a Korean resident of Japan, was accused of th crime. Kim held 13 people hostage in a nearby hotel, trying to have his story of constant intimidation and threats by the gangsters told, but eventually he was captured and sentenced to life imprisonment.

In 1974, during the height of the recession, a Japanese Korean family relocates to Tokyo to raise money and seek better treatment for their ill son.

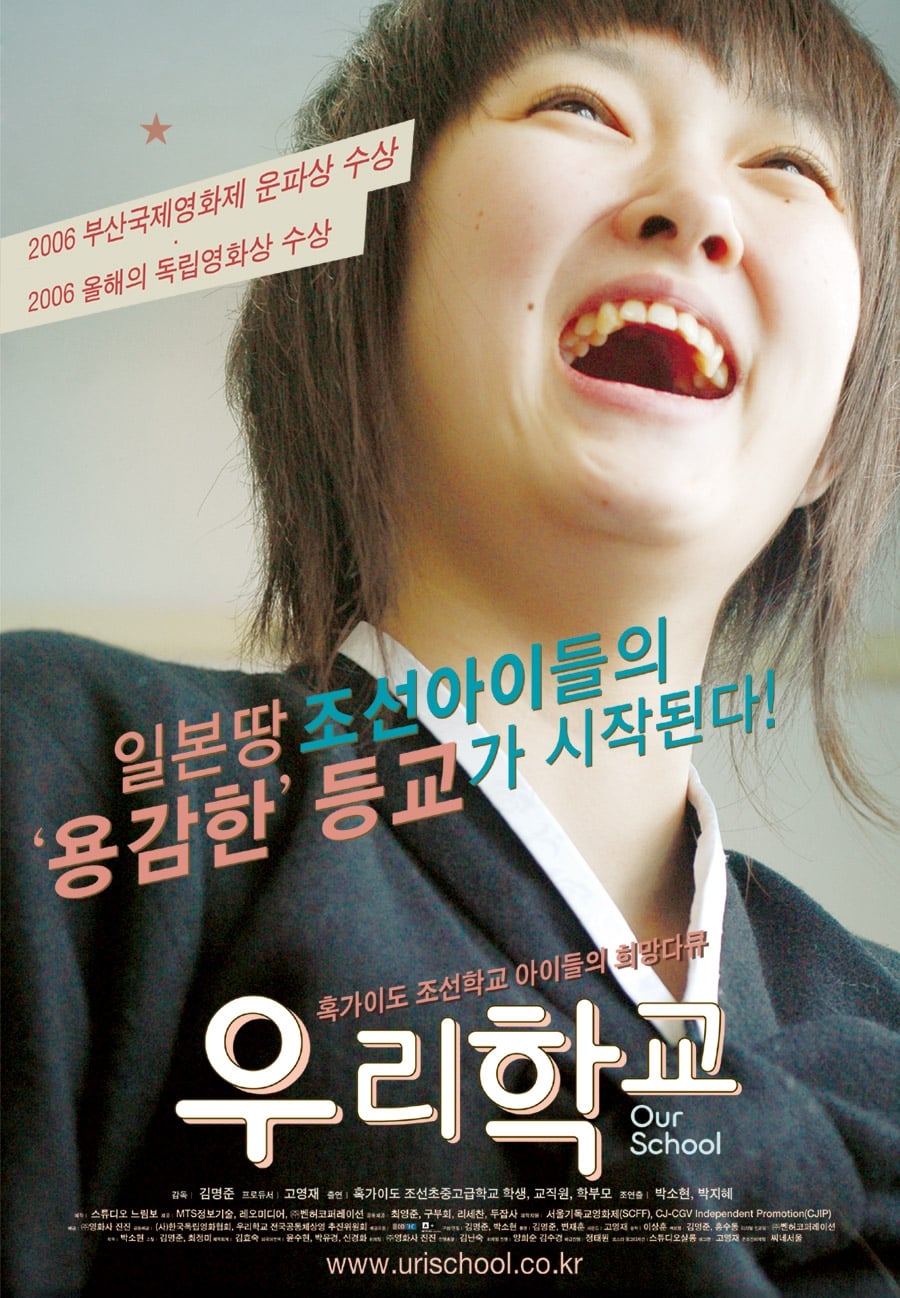

This documentary is about the 3rd and 4th generation Korean residents of Japan who are students of Chosen elementary, middle, and high school in Hokkaido. It follows the students through one year of the eventual 11 years` national education. Rather than focusing on special occasions or issues, it reveals what it is like to live in Japan as Korean-Japanese by describing their everyday lives.

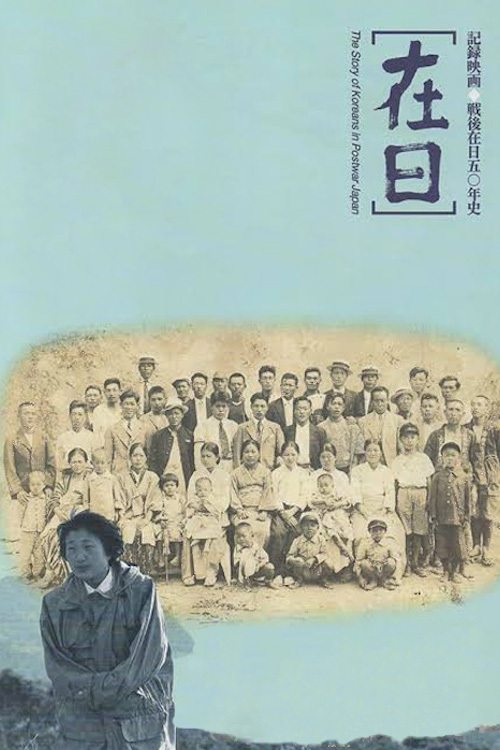

Portraying the fifty-year history of zainichi (long-term residents in Japan) Koreans after the liberation of Korea, traces of zainichi evoked in this film question the concepts of 'post-war democracy' and 'pacifism' in Japan. With copious stock footage and testimony, the first half of the film, "History," chronologically traces the various experiences of zainichi from Japan's defeat (Korean liberation) through 1990. The latter half, "People," focuses on first, second and third-generation zainichi respectively, vividly depicting how they live.

A spirited and brave fiction debut by Lee Sang-il, a Korean-Japanese filmmaker, that explores the taboo subject of the relations between Korean immigrants and Japanese in Japan.

An account of karate competitor Choi Yeung-Eui who went to Japan after World War II to become a fighter pilot but found a very different path instead. He changed his name to Masutatsu Oyama and went across the country, defeating martial artists one after another. This film concentrates on the period when he is still young, and developing his famous karate style, Kyokushin.

When poverty-stricken Korean-Japanese (Zainichi) discover there is valuable iron ore in the rubble of a destroyed shantytown they plan to haul it out for profit. Amidst this plan there is discrimination, war and an infatuation between a man and a woman, but like everything around them there and owing to the forces around them, there is as much chance that these may burn to ashes and be destroyed or be the beginning of something new.

By browsing this website, you accept our cookies policy.